Reading the Present through Wael Shawky’s Translation of History

By Fatima Blue

“I just want to analyse history through something that happened in the past to understand why the present is the way it is.”

Wael Shawky, interview with Talbot Rice Gallery, 2024

As a critic who grew up in a Shi’a culture deeply shaped by the rituals and narratives of the Karbala tragedy, encountering this event through the eyes of Wael Shawky, an Egyptian Sunni artist, was an experience both surprising and thought-provoking.

Within the Islamic world, this moment in history marks one of its most defining ruptures: the separation between Shia, who emphasize the Prophet’s lineage, and Sunni Muslims, who follow the consensus and tradition of his companions, two distinct interpretations of truth born from the same roots.

This difference made me curious to see how an artist from the Sunni world could reinterpret Karbala, a subject rarely explored in contemporary global art. What I found in Shawky’s work was not a religious lament, but a philosophical dialogue between faith, power, and memory, an attempt to understand a fundamental question:

Why do the same patterns of power and domination keep repeating and shaping our present fate?

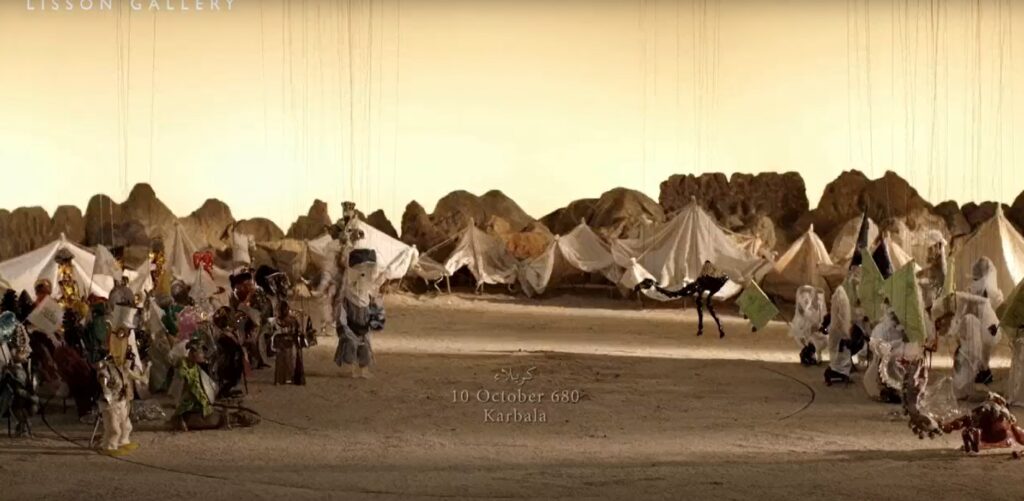

Shawky’s film The Secrets of Karbala (2015) is the final part of his grand trilogy Cabaret Crusades, a project inspired by Amin Maalouf’s book The Crusades Through Arab Eyes, aiming to retell the history of the Crusades from the perspective of Arab historians. In this retelling, history no longer speaks with the voice of the victors but of the forgotten. The film begins with the 7th-century event of Karbala, the crisis of succession after the Prophet’s death, which opened the first major division within Islam.

For Shawky, Karbala becomes a metaphor for the beginning of endless conspiracies and divisions within the history of power. Seeing himself as a translator of truth rather than its owner, Shawky suggests that the fall of Constantinople is not the end, but a tragic repetition of the same cycle that began in Karbala, a cycle where faith shows two faces: one of liberation and one of domination.

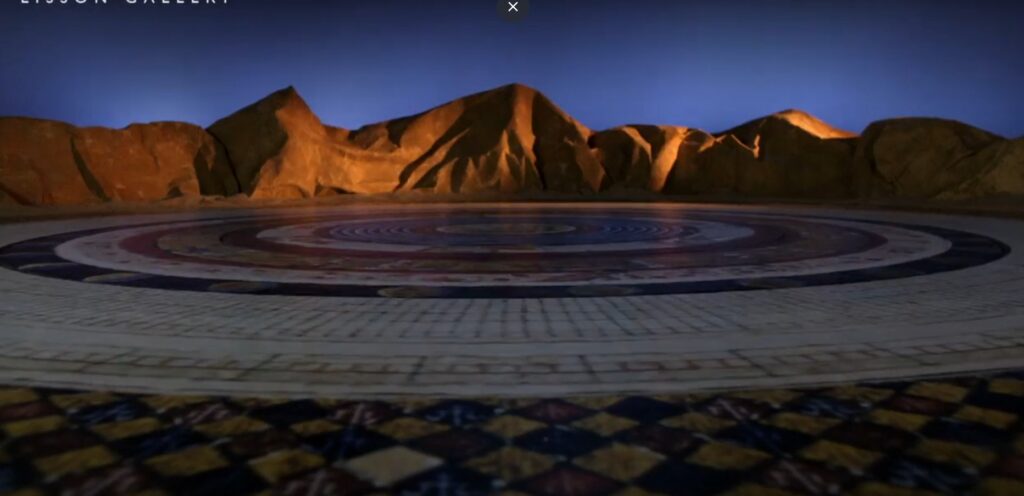

The film opens with a sequence of rotating circles, a constant motion that, in its simplicity, evokes many meanings. For me, as a critic who has lived within an Islamic society, this rotation recalls the tawaf, the ritual circling of pilgrims around the Kaaba (the cubic shrine at the heart of Mecca), a symbol of unity, harmony, and collective consciousness. As the camera slowly moves closer, from the wide, circular movement of the pilgrims to the faces of those in conversation, the collective unity begins to fragment, giving way to personal desires and the struggle for power.

This opening rotation becomes a visual metaphor for the historical repetition of ambition and domination, where faith, under the shadow of power, loses its spiritual meaning and turns into an instrument of legitimacy. In this single opening image, Shawky exposes the root of this repetition and poses a haunting question:

At what moment did human will lose its direction?

Karbala: A Global Metaphor for the Ideological Manipulation of Power

“We are all guided by something, sometimes not by governments, but by an idea.” With this way of thinking, Shawky takes Karbala beyond Islamic history and transforms it into a universal metaphor for how ideology manipulates power.

His intelligent choice of material, Murano glass puppets, becomes the key to this symbolism. These delicate, transparent puppets, reminiscent of traditional shadow plays, embody human memory: fragile yet luminous, always close to breaking but still carrying light.

The invisible strings that move them represent the unseen forces that direct human destiny. Through them, Shawky turns Karbala into an allegory of the human condition, beings suspended between freedom and control, acting within an endlessly repeating scene.

For Shawky, cinema is a collection of living paintings where every colour and movement reveals a new meaning. Using dramatic lighting and a palette of dark tones, blood-like reds, and aged golds, he builds a space that floats between dream and reality. These visual choices create a poetic distance that allows the viewer to reflect, not just observe.

The slow, ritualistic movement of the puppets transforms the scene into a “theater of de-sacralization”, each frame resembling a miniature painting that reconstructs history with emotional and spiritual distance. Thus, image in Shawky’s work is not a tool of narration, but a narration in itself a meditation on time, decay, and the erosion of meaning.

Along with its visual depth, the film unfolds in a ritual rhythm shaped by heroic, mournful music, a sound between sacred chant and historical narration. Composing the film’s music himself, Shawky employs traditional instruments and classical Arabic modes to build a heavy, sorrowful atmosphere that amplifies the tragic tone of the story. The use of classical Arabic language, rhythmic, poetic, and formal, gives the film a ceremonial feeling, as if history were being retold through an ancient rite.

Here, the viewer is no longer a passive witness to history but a participant in its reinterpretation, because music and language lift the work from documentary realism to a reflective ritual.

Shawky’s philosophical approach to history, deeply connected to Michel Foucault’s ideas, views history not as a sequence of events but as a battlefield of memory, where power operates not by force but through shaping beliefs and controlling narratives.

He translates this concept visually: the puppets and their invisible strings become metaphors for the unseen powers that write history. In The Secrets of Karbala, these figures are trapped in endless cycles of conflict appearing to act freely while actually being bound by ideological systems pulling their strings from behind the stage.

In my conversation with the artist, he connected this very idea to the Arab Spring, noting that even in an age where every moment is filmed, truth remains vulnerable to distortion. This reflection perfectly echoes Foucault’s idea of “power reproducing itself through narrative.”

For Shawky, art is not a representation of the past but an act of rewriting it a way to question the endless repetition of power.

Shawky’s use of puppetry to challenge the official narrative of history conceptually connects him to the French artist Christian Boltanski, especially in their shared interest in the fragility and manipulation of collective memory. While Shawky approaches it through ideology and theatrical history, Boltanski does it through archives and documentation.

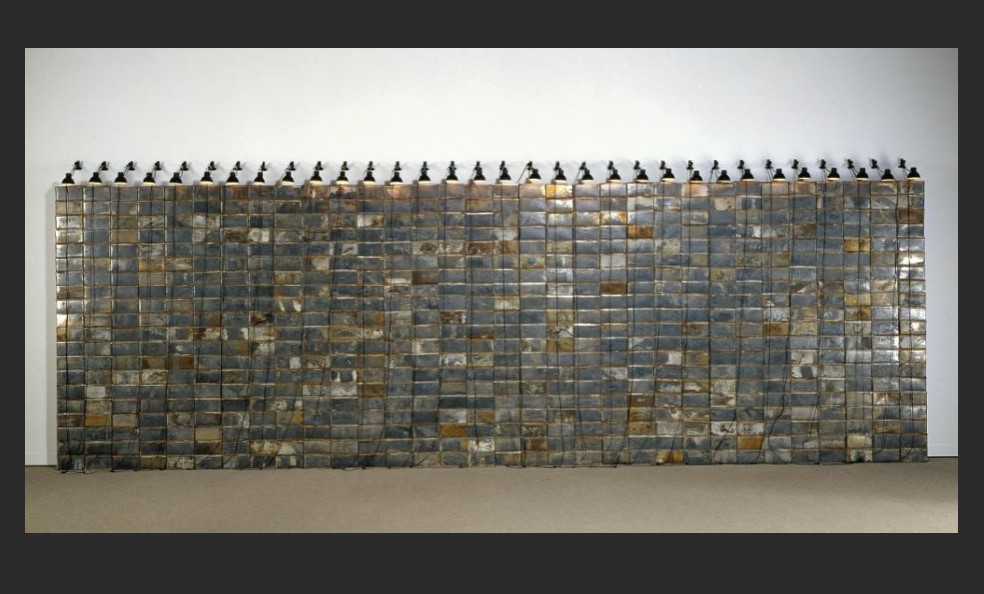

In The Secrets of Karbala, Shawky’s glass puppets expose the staged nature of historical conflict; similarly, in works such as The Archives of C.B., Boltanski fills metal boxes with countless photographs and documents, only to show how even archives symbols of truth, are incomplete, selective, and destined to forget.

Les Archives de C.B. (The Archives of C.B.) by Christian Boltanski

If Shawky’s invisible strings remove the agency of his characters, Boltanski’s archive systems erase the individual’s control over their own story. Both artists ultimately question the credibility of the tools we use to represent truth, whether it’s history or documentation and lead the viewer into a space of doubt, where memory is not the record of truth, but an endless reconstruction of forgetting.

In Wael Shawky’s world, history is no longer a dead past but a living conversation between imagination and reality. At a time when the shadows of old ideological conflicts once again fall over our world, his art reminds us that understanding the present is impossible without revisiting the recurring cycles of faith and power.

Through his fusion of philosophy, myth, and theatre, Shawky leaves us with one essential question:

Are we the makers of history, or merely the puppets moved by its invisible strings?