Whats Fueling Zao Wou-Kis Art Market Boom

ARTSY_The late Chinese-French painter Zao Wou-Ki has emerged as a major market force in the past decade. In 2018, his monumental triptych Juin-Octobre 1985 (1985) sold at Sotheby’s Hong Kong for $65 million, not only more than doubling his previous auction record, but also setting the record for any Asian oil painter and the most expensive work of art ever sold at auction in Hong Kong.

Although Zao was well-known throughout his lifetime, prices for his works have skyrocketed since his death in 2013. Juin-Octobre 1985 sold for $HK 18 million ($2.3 million) in 2005, meaning that one singular work increased in price by almost 30 times in 13 years. According to the artnet price database, his 23 highest-selling works have been sold since his death.

Zao Wou-Ki, Untitled, 1958. Courtesy of Sotheby's.

“It is no exaggeration to say that Zao is one of the very few Chinese Modern artists whose recognition has ascended to a truly global level,” said Sotheby’s head of sale for modern Asian art Felix Kwok.

Zao was one of the first Chinese artists to establish an international reputation, with demand for his work in the U.S. and Europe stretching back to the 1950s. Demand for his works in the Asian market caught up in the 1980s, and remains the strongest there. Emmanuelle Chan, Associate Specialist for Christie’s Asian 20th Century and Contemporary Art department in Paris, said she sees the vast majority of interest in Zao’s work coming from mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong.

Installation view of Zao Wou-Ki, at Gagosian, 2019. Photo by Robert McKeever. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ProLitteris, Zurich. Courtesy of Gagosian.

“When the Asian market started to take off, Zao Wou-Ki was one of the priorities among collectors,” said Gagosian director Jean-Olivier Després, who recently organized a show of Zao’s work at one of the gallery’s New York locations. “Because he had a strong group of collectors in Europe and America, and museums had been collecting his work for decades, his work was incredibly sought-after.”

Zao’s estate has also been in legal limbo until relatively recently. Following the artist’s death, his third wife and his son from his first marriage both sought control of his estate, which included up to $656 million worth of paintings. The courts ruled in favor of Zao’s third wife in 2017, leaving her free to exhibit or sell works from his estate. The Gagosian exhibition features a mix of works from the artist’s estate and private collections.

Zao Wou-Ki, 21.04.59 , 1959. Courtesy of Sotheby's.

Auction houses remain the biggest suppliers of his work, with Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Phillips each offering pieces by Zao in their October sales in Hong Kong, Paris, and New York. At Sotheby’s, the 1959 work 21.04.59 sold for $HK 104.5 million ($13 million), narrowly passing its high estimate of $HK 100 million ($12.7 million); Christie’s sold his 1989 work 6.2.89 for €2.7 million ($3 million), almost doubling its high estimate of €1.5 million ($1.6 million). And at the more affordable end of Zao’s price spectrum, on Friday morning Phillips sold two of his lithographs in its New York salesroom for $4,750 and $2,375.

In November, Christie’s will auction off two Zao paintings from renowned architect I.M. Pei and his wife Eileen’s collection during its Hong Kong sales. Zao’s 1970 work 27.3.70, a composition of whites, browns, and blacks, is estimated to sell for between $HK 38 million and $HK 48 million ($4.8 million and $6.1 million) at an evening sale on November 23rd. The other painting, Untitled (1950–51), will be offered the following day, with a pre-sale estimate of $HK6.5 million to $HK8 million ($829,000 to $1 million).

Inspiration in Paris

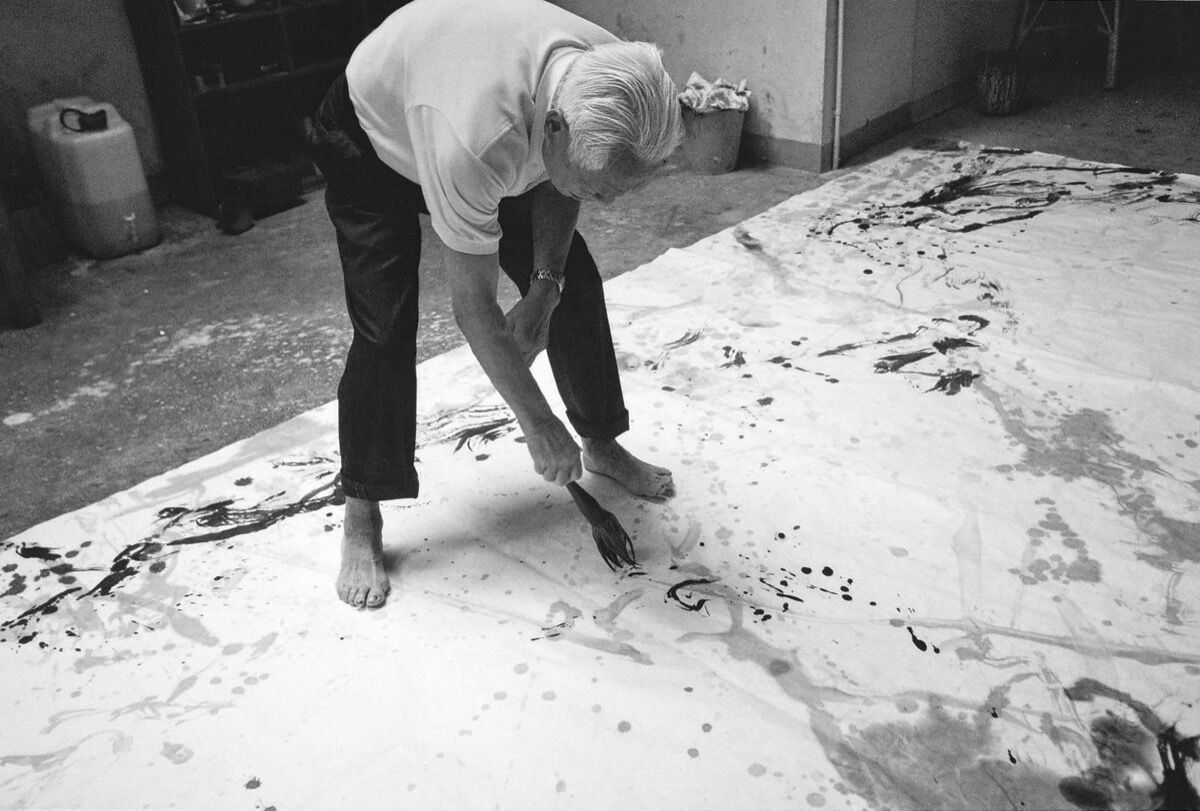

Zao Wou-Ki. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ProLitteris, Zurich, Courtesy of Gagosian.

Zao was born in Beijing in 1920 and studied traditional Chinese brush-and-ink techniques at the School of Art in Hangzhou. He learned from Lin Fengmian

, a pioneer of modern Chinese painting, and first exhibited at age 21 in Chongqing. When Zao arrived in Paris in 1948 he was captivated by Impressionism

and Expressionism, and began incorporating Western techniques into his work. He remained based in Europe for the rest of his life.

Although well-schooled in Chinese calligraphy, Zao initially tried to reject those conventions and work in a more purely European vein. Coming to terms with his Chinese heritage, he then shifted into his “oracle bone” period, inspired by ancient Chinese characters. Emilio Steinberger, senior partner at Lévy Gorvy, said he still sees this period as a strong focus for Asian collectors. Lévy Gorvy staged a show of Zao’s works in conversation with work by Willem de Kooning in 2017, and has worked with Zao’s foundation and estate.

“Since we began organizing that show, there has been much more interest amongst all people—collectors, museums, critics,” Steinberger said.

Zao Wou-Ki, 7.3.70, 1970. Courtesy Christie’s Images Ltd.

In Paris, Zao met a number of artists who shared his interest in abstraction, including the French painter Pierre Soulages, but also other expats like Joan Mitchell and Jean-Paul Riopelle. In 1957, Soulages took Zao to New York, where he was inspired by the Abstract Expressionist

works of Franz Kline, Philip Guston, and Adolph Gottlieb. He showed with some of the most prominent galleries of the day, such as the New York-based Kootz Gallery and Paris dealer Pierre Loeb.

After his visit to New York, Zao moved into his “hurricane period,” where he moved away from more figurative works in favor of bold, abstract paintings that explored space and structure. Works from this period, spanning from roughly 1959 to 1972, have long been the most sought-after among collectors of Zao’s works, with his work 29.01.64 (1964) fetching $25.9 million at Christie’s in 2017 and holding his auction record until last fall.

Zao’s triptychs have taken center stage in recent years, partly due to their size: at 33 feet in width, Juin-Octobre 1985 was the largest oil painting he ever made; his second-largest painting ever to come to auction, Triptyque 1987-1988 (1987–88), fetched $22.6 million at a Christie’s auction earlier this year. For Steinberger, the huge scale and ambition of Zao’s late-career works gives them tremendous appeal and wall power.

“His 1980s and ’90s works are as intense as his ’60s, and it was just a factor of getting people in front of them,” he said.

“The father of modern Chinese art”

Zao Wou-Ki, Untitled, 1950–51. Courtesy Christie’s Images Ltd.

Zao’s ever-expanding circles of friends across three continents not only provided him with inspiration, but in some cases advanced his career. The Gagosian show focuses on the artist’s lifelong friendship with renowned architect I.M. Pei. Pei encouraged Zao to embrace ink in his work, and the pair traveled to Egypt together to research Pei’s Louvre pyramid project.

Zao has also benefited from sustained institutional interest, with his works being collected by museums including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Centre Pompidou, and the Tate Modern. Last year, the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris presented the first major show of Zao’s work in the French capital in 15 years, focusing on his larger works. The exhibition included several works in ink that had never been displayed before, and that are currently on view in the Gagosian show.

Kwok suggested Zao’s success could signify a growing market for modern Asian art market overall. “The surge in popularity of Zao Wou-Ki can be viewed as part of a broader picture—the rise of modern Asian art as a collecting category,” he said. “It’s more than a personal success story.”

But others cautioned against tying Zao’s success too closely to growing interest in Asian art more broadly. Chan said she sees collectors buy work by Zao who do not seem interested in many other Asian artists, though he has certainly influenced other contemporary Asian artists.

“Zao Wou-Ki is regarded as the father of Chinese modern art and as a model for a lot of Chinese artists today,” she said.