Yayoi Kusamas Radical Work Goes Far beyond Her Infinity Rooms

ARTSY_Although Yayoi Kusama’s storied, international career spans over five decades, much of her oeuvre has been eclipsed by a single body of work: the “Infinity Mirror Rooms.” Kusama created the series’ first work, Infinity Mirror Room—Phalli’s Field, in 1965 and has since produced more than 20. These immersive environments project the appearance of infinite space and the repetition of the viewer using various scales, colors, and motifs.

Images of Kusama’s “Infinity Mirror Rooms” proliferate on social media as much as our own images multiply within the artworks themselves—and they’ve been known to draw massive audiences. As David Zwirner prepares to mount the surefire blockbuster “Yayoi Kusama: EVERY DAY I PRAY FOR LOVE,” which includes a new “Infinity Mirror Room,” the gallery has issued a warning about expected wait times of more than two hours.

However, as the current show at ICA Boston “Beyond Infinity: Contemporary Art After Kusama” demonstrates, Kusama’s legacy extends far beyond a single body of work. That exhibition complements the concurrent show, Yayoi Kusama: LOVE IS CALLING, which celebrates the museum’s acquisition of Kusama’s largest “Infinity Mirror Room”to date.

Yayoi Kusama, LOVE IS CALLING , 2013. Photo by Ernesto Galan. © Yayoi Kusama. Courtesy of David Zwirner, New York; Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore/Shanghai; Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

Organized by Ellen Tani, “Beyond Infinity” charts Kusama’s radical legacy across various mediums and her influence on generations of artists. “I felt that if we were going to get people seeking that experience or that Instagram moment, this was an opportunity to give some context to who this artist is,” explained ICA chief curator Eva Respini. She hopes to engage audiences with Kusama’s ideas around “performance, repetition and labor, and a celebration of movement and the body…and how they’ve been really influential to the artists who have come after her.” The exhibition also includes the organic forms of Kusama’s contemporaries including Eva Hesse and Louise Bourgeois

, as well as a later generation of artists exploring dynamic performance techniques and infinite repetition, such as Nick Cave and Josiah McElheny.

Understanding the breadth of Kusama’s oeuvre cements her as an icon who has had one of the most influential, transdisciplinary practices of the last century. Here, we take a look at some of her most important bodies of work, beyond the “Infinity Mirror Rooms.”

Painting

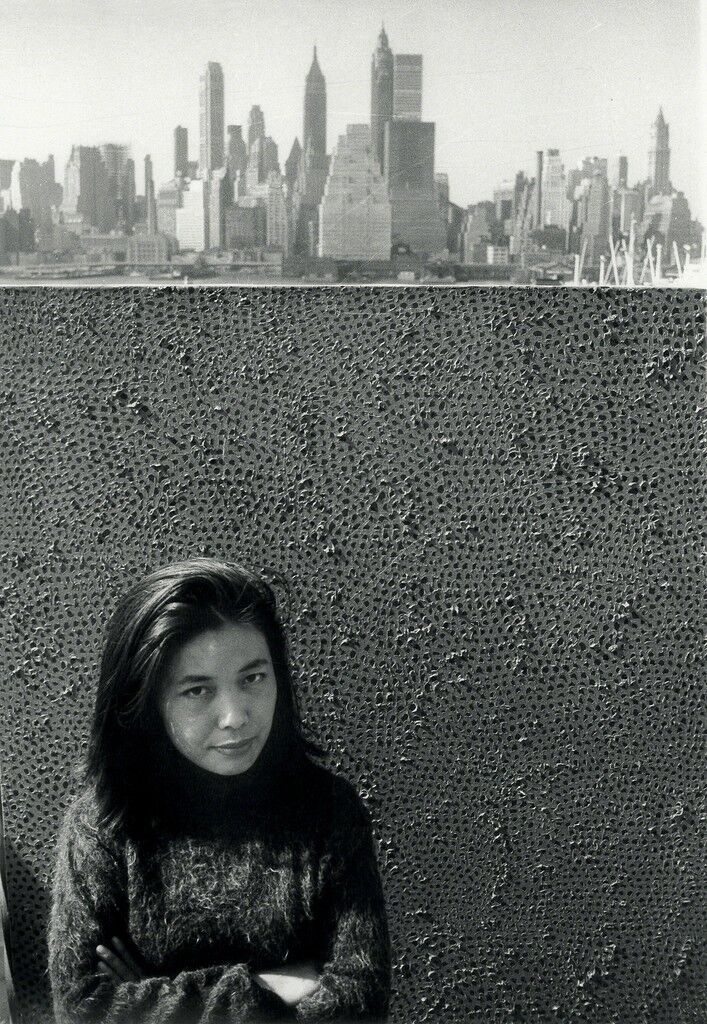

Yayoi KusamaYayoi Kusama with one of her Infinity Net …

"Yayoi Kusama: In Infinity" at Moderna …

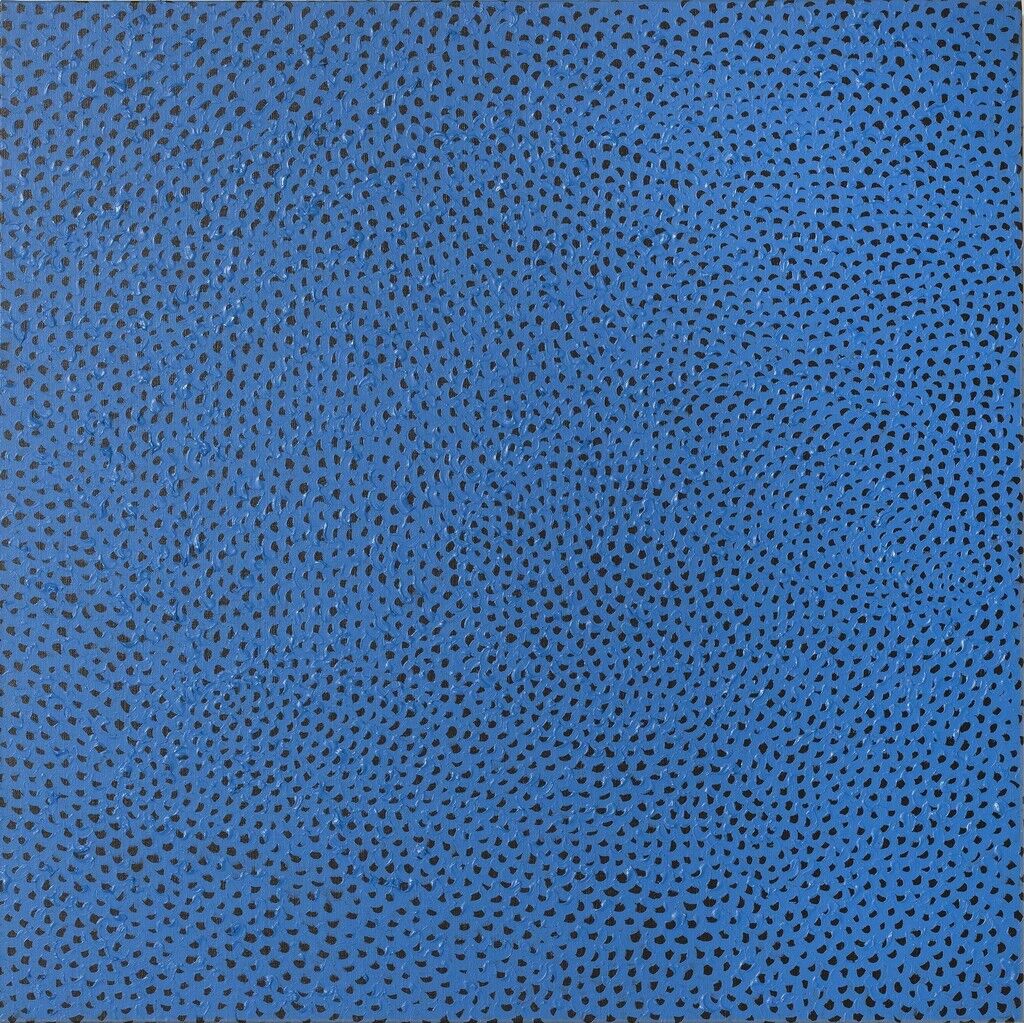

Yayoi Kusama Infinity-Nets PEAA, 2013

Helwaser Gallery

Kusama began to explore ideas of infinity by challenging the confines of the canvas’ four edges. Before moving to New York in 1958, she was schooled in traditional Japanese Nihonga painting. During the beginning of her time in the United States, she experimented with Surrealist techniques such as frottage and decalcomania; however, it was her “Infinity Nets” that truly began to distinguish Kusama from other painters. Crescent-shaped, single-colored brush strokes coalesce over a solid ground to form “nets” that ebb and pulsate hypnotically. Kusama has described these paintings as “very large canvases without composition—without beginning, end, or center.” She creates lattices of pigment that blur the boundaries of negative and positive space. Equally as immersive as her canvases was her process: Kusama claimed to work 50 to 60 hours non-stop on paintings.

Her 1959 solo New York debut at Brata Gallery contained five paintings from her “Infinity Net” series and received high praise from none other than artist-critic Donald Judd

, who would become a dear friend of Kusama’s. Judd began his Artnews review with: “Yayoi Kusama is an original painter.” He went on to describe the paintings as suggestions of “an analogy to a large, fragile, but vigorously carved grill or to a massive, solid lace.” Judd would even purchase one of the works for $200.

In 1961, Kusama exhibited White x.X.A,a painting that spanned the entire height and length of a wall at Stephen Radich Gallery. This totality shifted the notion of infinity in her painting practice from an optical effect to a corporeal experience. Viewers started to relate to her paintings in terms of their own bodies and the architecture of the exhibition space. Though these paintings were not completely immersive, they foreshadowed the mise-en-abyme qualities she would achieve in later installations.

Sculpture

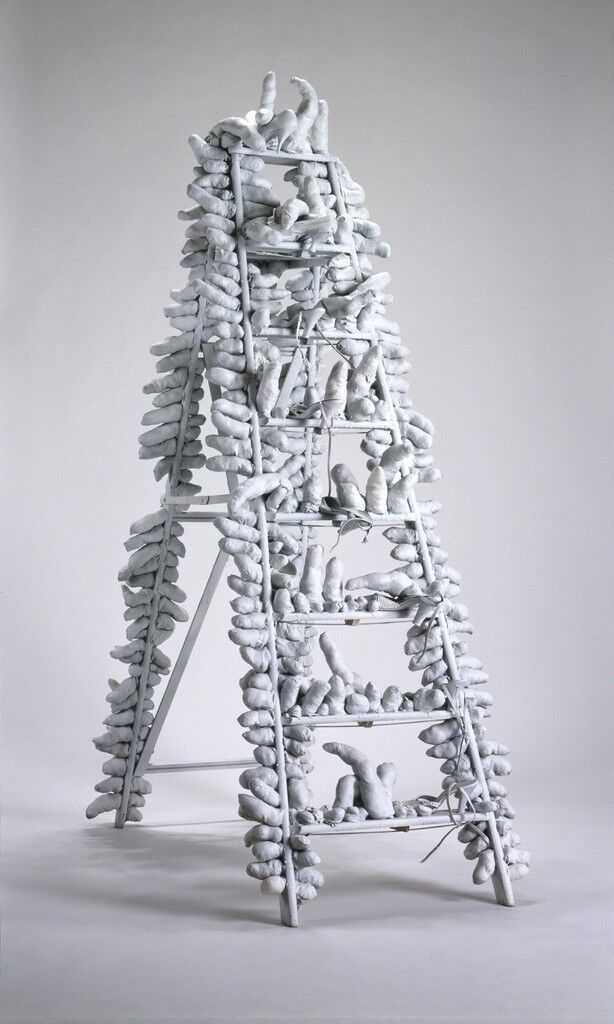

Yayoi Kusama Traveling Life, 1964

"Yayoi Kusama" at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, …

Yayoi Kusama Phallic Girl, 1967

"Yayoi Kusama" at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, …

In her “Aggregation” series, Kusama translated endless repetition into the third dimension. These sculptures of everyday objects and furniture fester with hand-sewn phallic protrusions. Kusama linked the repeated phallic forms to her fear of sex. “By continuously reproducing forms of things that terrify me, I am able to suppress the fear,” she wrote in her autobiography, “and lie down among them. That turns the frightening thing into something funny, something amusing.”

Kusama created Accumulation No. 1 (1962), a phallus-covered armchair, in the studio building that she shared with Claes Oldenburg, who made soft sculptures of domestic objects around the same time. She would also expand on this technique with Aggregation: One Thousand Boats Show (1963)—in which a phallus-covered boat was placed in a room wallpapered with 999 boat posters—to produce her first immersive installation. Kusama’s “Aggregation”series foreshadows the sprawling everyday objects that comprise the installations of Tara Donovan. Theseries also echoes the horror vacui quality Kusama would realize in later work, such as Infinity Mirror Room—Phalli’s Field (1965).

Fashion

Kusama transformed her sculptural motifs into wearable fashion designs. In the 1960s, Kusama started Yayoi Kusama Fashion Company to reach sizable audiences. The 1965 piece Blue Coat is covered with protrusions of brightly colored, phallic forms, which imbue a surreal, sexual quality into an everyday garment.

Yayoi Kusama Untitled, 1968

MASAHIRO MAKI GALLERY

“The mass media reported about us big time,” Kusama later recalled in an interview with Akira Tatehata. “We did fashion shows and had a Kusama corner at department stores. Buyers from big department stores came and selected 100 of this, 200 of that, although they only bought the more conservative styles. The radical vanguard items that I poured my energy into sold little in the end.” Her radicality certainly found more success in the art world than in the fashion industry. Although Kusama was widely recognized for her clothing, she became even better known for her nudity.

Performance

Kusama’s variety of performances spanned the orgiastic and the activistic. In 1968, she staged “Anatomic Explosion” happenings that included nude “Body Festivals” at sites such as Wall Street, the Brooklyn Bridge, and the New York Stock Exchange. Participants stripped down and burned American flags to protest the Vietnam War. Kusama would alert the press to make sure the events were well documented, as her lawyer looked out for approaching police. Kusama yelled: “Stock is a fraud…money made with this stock is enabling the war to continue…[o]bliterate Wall St. men with polka dots on their naked bodies!”

She extended her voice all the way to the oval office in a letter to Richard Nixon. “Let’s forget ourselves, dearest Richard, and become one with the Absolute,” she wrote. “As we soar through the heavens, we’ll paint each other with polka dots, lose our egos in timeless eternity, and finally discover the naked truth: You can’t eradicate violence by using more violence.” During one of her performances, she also distributed an open letter to Nixon that read: “Anatomic explosions are better than atomic explosions.”

Kusama’s performances embodied “self-obliteration,” her belief that positives and negatives of endlessly replicated infinite patterns blurred to obliterate notions of the self.

Writing

Kusama not only mastered the visual realm, but the written word as well. Her first novel, Manhattan Suicide Addict, published in 1978 after her return to Japan, provided a fictional account of her life as a struggling artist in the 1960s. Kusama has since published over 15 volumes of novels, composed several songs, penned an autobiography, and published an anthology of poetry.