artsy_The art world always seems to need a punching bag. Often, it’s an artist who is both a popular favorite and a market darling; someone whose work is so rabidly beloved by the masses that they can’t possibly be serious. Brian Donnelly, a.k.a. KAWS

, might be the most prominent recent example of this phenomena.

KAWS is a global star—2.3 million Instagram followers and counting—who so many establishment critics talk of with disdain, if they talk about him at all. Witness The Art Newspaper, for instance, which sets the tone by lamenting the “sheer conceptual bankruptcy” of KAWS. “Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol, Sherrie Levine, Sarah Lucas

. These are the artists who waged war on elitist, bourgeois models of aesthetic and conceptual value,” the author writes, before adding that KAWS “does not belong to this lineage”—as if that were ever his chief ambition.

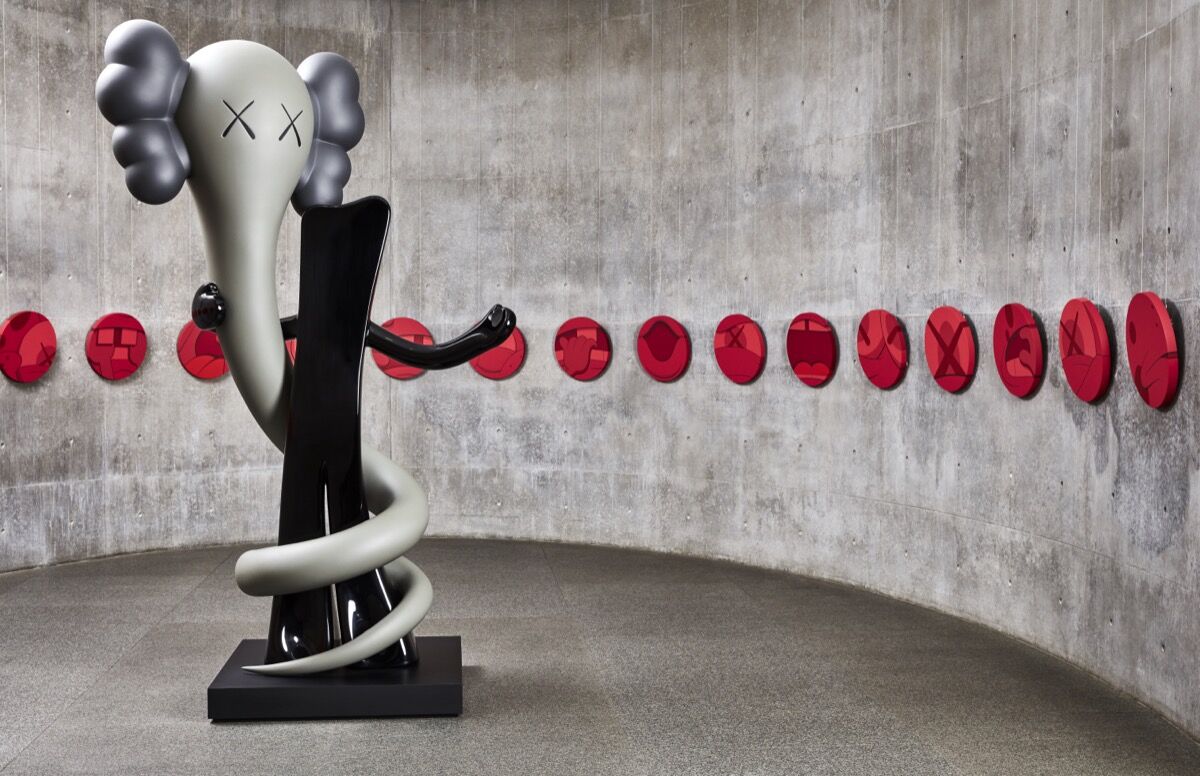

Installation view of KAWS, BORN TO BLEND, 2013, and BLUSH, 2012, at the Modern Museum of Fort Worth, 2016. Photo by Matt Hawthorne. Courtesy of the artist.

KAWS has had a long and winding career—one that began as a street artist, throwing up tags and culture-jamming phone booth advertisements in New York with his own cartoonish iconography. His first solo show was at the Parisian boutique, Colette; he’s now represented by Skarstedt Gallery in New York, a tony Upper East Side establishment that works with artists like David Salle and Christopher Wool

. KAWS has always straddled all worlds—producing collectible toys; collaborating with Uniqlo on clothes that set off mass hysteria; making auction news; and stealing the show at Frieze London.

It’s possible that, 50 years from now, art history will look back on KAWS as someone who further troubled the line between art and commerce in intriguing ways. At the same time, this isn’t what makes him truly interesting, and to discard his entire output as frivolous—so many silly cartoons with X’ed out eyes, signifying nothing—is just lazy. Below, a few reasons to take KAWS seriously—not as a savvy entrepreneur or an icon of hypebeast culture, but as an artist, plain and simple.

His largest-scale sculptures are a new kind of Land Art

KAWS, HOLIDAY, 2019. Photo by AllRightsReserved. Courtesy of the artist.

KAWS, HOLIDAY, 2019. Photo by AllRightsReserved. Courtesy of the artist.

Eugenie Tsai, a curator of contemporary art at the Brooklyn Museum, oversaw “KAWS: ‘Along the Way,’” a KAWS survey that opened at the institution in 2015. More recently, she was thrilled by KAWS’s “KAWS: Holiday” project, for which the artist installed a 37-meter sculpture of one of his “Companion” figures in spots around the world.

“Social media enabled me to observe the gigantic sculpture, slumbering at the foot of Mt. Fuji through rain and shine, through day and night. Throughout it all, the mountain seemed to shrink,” Tsai said. “KAWS uses scale to shift and rearrange our perception of our immediate, outdoor surroundings, in a way that’s comparable to what some of the artists making Earthworks in the 1960s were doing.” Whereas Land artists like Michael Heizer and Robert Smithson

relied on documentation in magazines to publicize their remote projects, Tsai said, KAWS is able to use platforms like Instagram, ensuring that millions of strangers can virtually experience his ambitious interventions.

The sculptures also have an unexpected emotional range. “KAWS: Alone Again,” a recent KAWS exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD), included five sculptural figures posed around the semi-darkened exhibition space. The works “are rooted in art history, aware of the past,” said MOCAD executive director Elysia Borowy-Reeder, who curated the show. “There’s a lot of melancholy in the figures. You do feel the sense of loss, of being alone, when you look at them.”

His skills as a colorist shouldn’t be underestimated

A typical KAWS work is not a wallflower; it loudly stakes its claim on your eyeballs with the most energetic colors possible.

“Brian is a sophisticated colorist,” said artist Julie Curtiss

, a rising star in her own right who previously worked in KAWS’s studio for several years. “His colors are bright, but not out-of-the-tube.” All of the artist’s acrylic pigments are made-to-order by Golden Paints. “He picks almost all of his colors ahead of time,” Curtiss explained, “everything is in his head, and it’s dead on—which puzzles me, as a painter, because I’m often wrong about color combinations and constantly need to make adjustments.

“Colors are the soul of his paintings,” she continued, noting that KAWS will pick a palette that can convey the mood for a whole series. “Sometimes, it looks as if he applied a colored filter over an entire painting, as if you’re looking at it with tinted glasses on.” She noted that the way he alternates warm and cool colors makes his compositions more vibrant. At times, at the studio, she recalled, “we’d have a hard time recognizing a color because of its placement next to another one; that would completely change our perception of it—a kind of optical illusion.”

He’s a collector who supports other artists

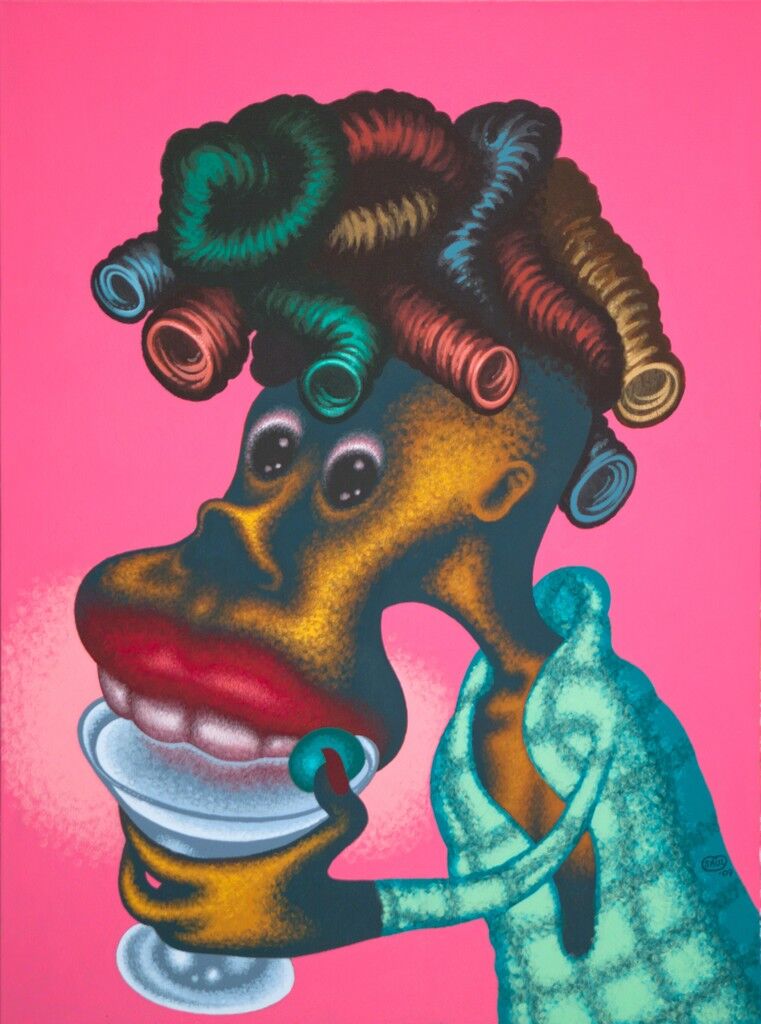

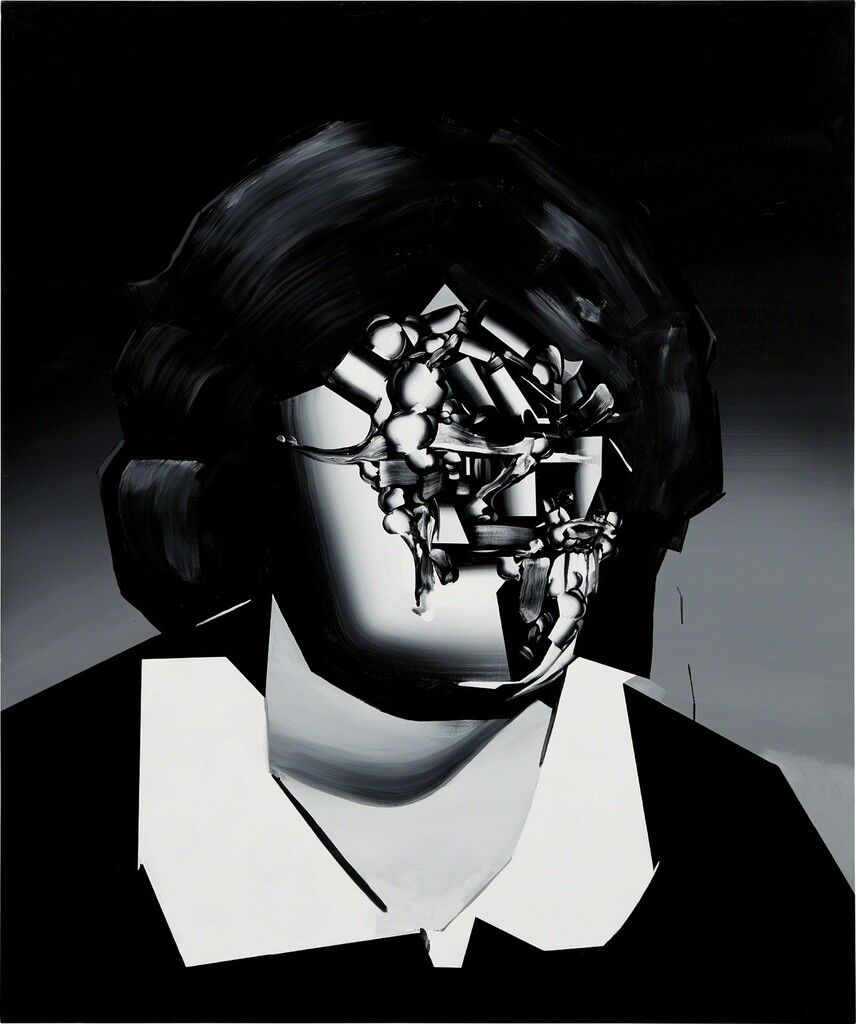

Peter SaulWoman Drinking Martini, 2009

Tomoo GokitaGeneral Emotionality, 2008

Phillips

When your paintings are selling for $14.7 million at auction, it’s safe to assume that you have a bit of your own money to burn. And KAWS has certainly shared that wealth, earning a reputation as a dedicated collector who supports his peers.

In 2017, Architectural Digest toured the home he shares with his wife, artist Julia Chiang

, and kids. It’s jam-packed with pieces by Gaetano Pesce, Tomoo Gokita, Carroll Dunham

, and Martin Wong. KAWS’s collection is also heavy on Peter Saul

(“I have Sauls everywhere,” he told the New York Times).

When Curtiss worked in the KAWS studio, she had a first-hand look at some of his latest purchases. “It would range from the next-door, emerging artist—sometimes friends!—to Outsider art

, street art, design objects, and more internationally recognized artists like John Chamberlain

.” She noted that his collection of Chicago Imagists

is particularly outstanding, including artists Ray Yoshida, Gladys Nilsson, and Karl Wirsum

. “Brian is an artist who collects artists,” Curtiss added. “His interest is genuine. Not only does he support a wide range of artistic communities, but he creates a historical context for these works to exist in.”

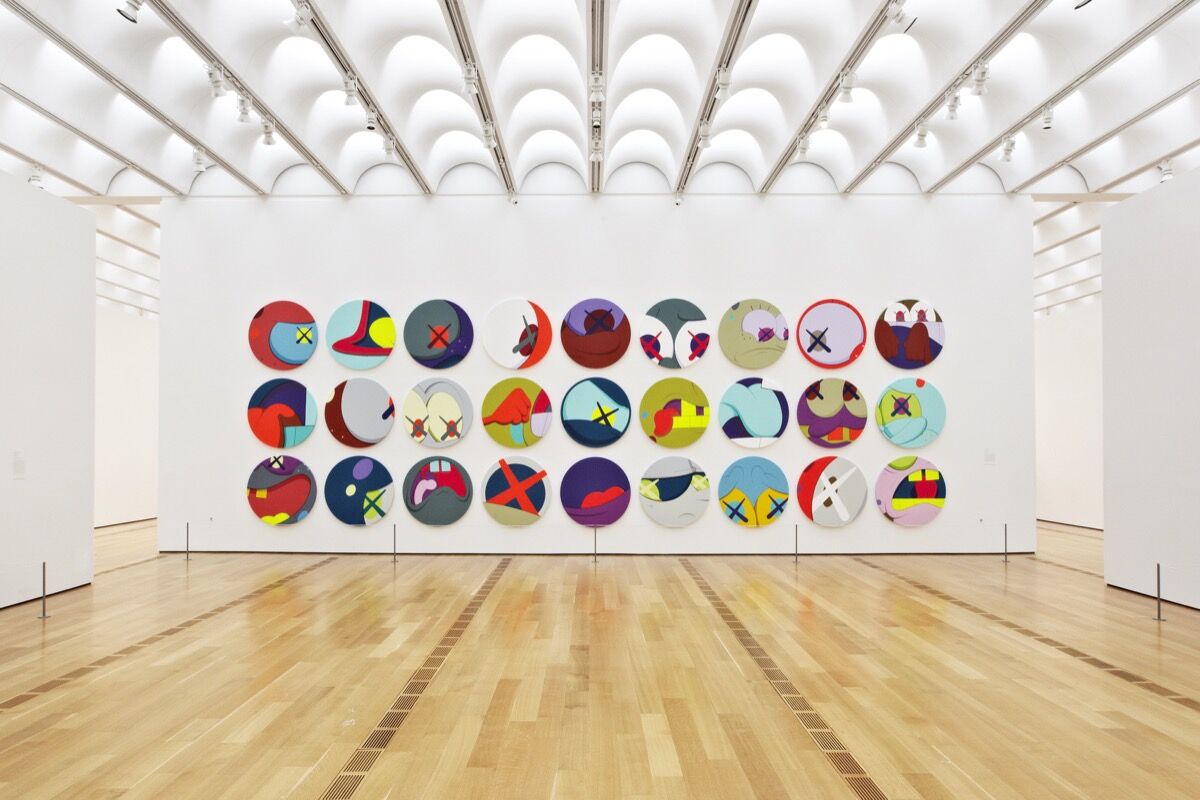

His tondos are irresistible

Installation view of KAWS, GONE AND BEYOND, at The High Art Museum, 2012. Photo by Adrian Gaut Courtesy of the artist.

KAWS often ditches the rectangle in favor of shaped canvases—including ones that borrow the silhouettes of popular cartoon figures. But I’m most enamored of his experiments with the tondo

, a tradition of painting on a round surface that dates back to the Renaissance.

KAWS uses this circular format to isolate cropped details of a face—a single eyeball, a hand—or to cram in a buzzy assortment of colorful, abstract marks. Often installed in a long row, or an imposing grid, these works end up looking like discrete portholes, each offering an almost random, bite-sized blip of KAWS’s energetic style. They’re fun, but also formally astute.

He’s an impressive pop-culture cannibal

KAWS, THE WALK HOME.., 2012. Courtesy of the artist.

I’ll admit it—KAWS has made a few paintings I just can’t stand. But in many cases, KAWS proves himself to be an inventive and uncanny sampler of pop culture, breathing weird new life into familiar figures and scenes. There’s Chum, for instance, a not-so-distant cousin of the Michelin Man, as well as SpongeBob SquarePants, whose visage is often chopped up and remixed in wonderfully deranged ways. Charlie Brown, Snoopy, and mutant versions of the Smurfs also make frequent cameos.

KAWS, IN THE WOODS, 2002. Courtesy of the artist.

“Like Andy Warhol

—who painted Marilyn Monroe because she was an American icon, so universal that she was instantly recognizable to everyone, KAWS took images from The Peanuts because they represented ‘part of being a kid in America,’” said Per Skarstedt. “He wanted to make images that could be easily understood.” That can, of course, be read as a sort of pandering to the lowest common denominator. But it could more generously be seen as a tactic, exploiting nostalgia and familiarity. Consider KAWS’s epic triptych In the Woods (2002), which samples a bucolic scene from Disney’s Snow White. The artist’s palette here is uncommonly subdued, with just three colors. The zombified version of an innocent scene has a real sense of pathos.

“KAWS deceives the viewer with his familiar language of vintage cartoons, forcing us into an anxiety-ridden scene occupied by an urgently emotive cast of characters,” said Borowy-Reeder of MOCAD. Easily understood? Sure. But meaningless, or “conceptually bankrupt”? Hardly.

And he’s an even more talented abstract painter

KAWS, Not yet titled, 2019. Courtesy of Skarstedt Gallery.

While many would think of KAWS as a purely figurative painter, his abstract or semi-abstract works are arguably more interesting. Certain works—like Perils and Rack and Ruin (both 2008)—resemble Hard-edge paintings whose geometries were rudely crashed into by errant cartoon characters. With abstraction, KAWS is able to capture and freeze a certain kinetic energy. Often, his paintings focus on what appears to be a particular detail of a larger composition, zooming in so abruptly that the viewer loses all her bearings. In a yet-to-be-titled 2019 painting, on view in a group show at Skarstedt Gallery this summer, streaks and splatters of purples and pinks criss-cross the canvas, and a Day-Glo yellow band shoots up the canvas’s edge—a graffiti-inflected update on Barnett Newman’s zips. The gallery, eager to connect KAWS within the wider narrative of contemporary art, has savvily hung the work across from an abstraction by Albert Oehlen

. It’s time that the critical establishment also lightens up a bit and accepts that KAWS is indeed part of this broader conversation, not just a populist flash-in-the-pan